Since I’m on episode #3 now, I’m going to start promulgating Ep #1 for free here and there, like a little fairy…

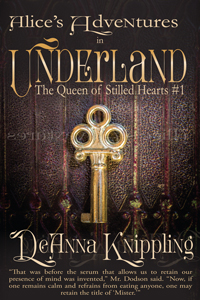

Alice’s Adventures in Underland: The Queen of Stilled Hearts #1

(Now free at Smashwords, Gumroad, Apple, and Kobo; other sites in progress here: Amazon, B&N.)

Foreword

Pride, Prejudice, and Zombies came out in 2009.

I suspect the first day I so much as heard of it, I had the idea for this book in the back of my mind. In 2011, I wrote the first draft for a NaNoWriMo project.

I have been terrified to do anything with it ever since. The Alice books are my favorite books ever. I have combed through The Annotated Alice more times than I can count. I love the Tenniel illustrations. I’ve poured over biographies (Morton Cohen’s Lewis Carroll: A Biography is the one I drew on most strongly here), I’ve wondered at the missing diary pages, I’ve gasped at the thought of the real-life Alice running around with the Queen’s children, and I’ve goggled at the surrealness of Alice in Sunderland by Bryan Talbot. I debated with myself for hours over whether to attempt to use British spellings and grammar and whatnot (I decided against it for the time being but am working on it).

And the cover.

There’s an image I wanted to use. A pair of them. But I’ve had trouble getting good digital copies of the photographs at rates I can afford, so that may have to wait.

Both of the pictures are by Charles Dodgson, Lewis Carroll’s original. The Dodo.

One picture’s from 1857. I can’t seem to find the first picture that Dodgson took of the Liddell girls (in 1856), but there’s one from 1857 that captures what I want. A little girl sits with her hands in her lap, staring at the camera. She’s got this look on her face. “Oh come on, pull the other one, it’s got bells on.” She’s no curly-haired, tame blonde thing. She’s dark-haired and willful looking. She’s trouble.

The other one’s from 1870, the last picture that Dodgson ever took of her. An upper-class young woman slouches forward in the chair as if no effort of will could make her sit up straight again. She glares at the camera, accusing it–of what, we’re not sure. She’s eighteen and her mother wants her to sit for a portrait suitable for advertising her on the marriage market. It’s the same year that Dodgson is writing Through the Looking-Glass, the same year the White Knight falls off his horse, endlessly, while escorting the fictional Alice towards her Queendom; inevitably, she leaves him behind.

I can’t escape the idea that there’s something intertwined between the life of the real Alice and the fictional one; that the books are a kind of instruction manual, a code–a message to a stubborn, willful upper-class girl about how to survive the madness of the Victorian era, with its standards and hypocrisies.

This isn’t a book about zombies running rampage over England (although they do a bit) or about Alice slaughtering her way through oncoming hordes. Nothing wrong with that, but it wasn’t the story I meant to tell. This is more of a teatime with zombies story, quite civilized, until it isn’t.

I apologize for the errors (they’re all my own, which is what makes them so terrifying) and hope that, in my retelling, I haven’t done the characters and people herein a disservice.

Chapter One

(1856; Age Four)

“Alice! Hold still this instant!”

Mother pinched the top of her ear with sharp fingernails. She was annoyed because the small side parlor hadn’t been dusted properly. Edith was only a baby, but Ina had done her chores in half a moment, then refused to help even though she didn’t have as much to do, in addition to which Alice had been told to stay off the chairs, which meant that Alice had only dusted what she could reach from the floor and of course Mother always looked at things from such an incredible height that she never did see the places where Alice had cleaned. Mother said that even the best kind of people ought to have responsibilities when Alice had protested that she wasn’t a maid.

“Ow!” she cried. “Stop pinching me.”

“And shush.” Her mother picked up the brush. “We’ll just have to hope that dust won’t show in the photograph when Mr. Dodgson comes to take your picture. What were you thinking?”

“Ow-wow-wow!” The harder her mother brushed her hair, the louder she shouted, until Ina and Edith had their hands over their ears.

“She won’t let you go until all the knots are out of your hair, Alice,” Ina said. “It’s your punishment for not brushing it yourself.” She sat in one of the pretty chairs with the flowers on the cushions with her legs crossed at the ankles and a book in her lap.

Alice rather thought that Ina needed a handful of mud put down her pockets, because she seemed so very older-sisterish and tidy, which must have been uncomfortable.

“What about Edith? She has knots in her hair.”

“She’s only a baby,” Ina said, then turned the page in the heavy book. Alice wasn’t allowed to read books by herself any longer; one accident two years ago, when she was quite younger than she was now, and Mother had flown into an unforgiving rage.

At any rate, none of them wanted to tell Father if anything should happen to one of the books, which meant that keeping Alice (and Edith) away from them was rather safer.

“Don’t worry about Edith’s hair, Alice,” her mother yanked the brush again. “Worry about your own.”

“Why can’t Miss Prickett brush my hair?” Alice asked, speaking before she thought, as usual. “She brushes better than you do.”

Ina’s eye flicked toward Alice while she turned another page. Edith banged a wooden spoon on the leg of the chair, trying to crush the dust-motes that sparkled in the air. In a second, Mother had taken the spoon from her, dumped Alice over her lap, and beat her several times with the spoon.

“Don’t…talk…to me…about…Miss Prickett!” her mother exclaimed.

Alice bit her lip. Crying out now would only make things worse, because then she would be sent to explain herself to Father.

“Oh!” her mother cried. “Even your underthings are brown with dust. Alice! What kind of manners is Miss Prickett teaching you?” And then her mother hit her again.

Ina glanced at Alice again, and Alice understood that now was the time to submit to Mother without another word or whimper: Miss Prickett was something precious, and not to be dragged into Mother’s attention more than necessary.

“It’s all my fault, Mother. I’m rather wild, you know.”

Mother released her, brushing her skirts down for her. “If you can’t behave, then I shall tell Miss Prickett that it is time that she was replaced with someone sterner.”

“Yes, Mother. I shall be quite good.”

Mother nodded.

If Alice’s contriteness wasn’t entirely genuine, it wasn’t entirely false, either. The children were all fond of Miss Prickett, even though Alice’s fondness tended to show itself as pranks and teasing.

Mother was not one to cross.

—

Eventually, Mother left them in the hot parlor, which contained nothing that might muss their hair, with strict instructions not to move a muscle. Alice couldn’t help pointing out that they would soon suffocate if they weren’t allowed to breathe, but her mother had ignored her and swept out of the room, her skirts brushing against the carpets and the furniture with a heavy swish that scattered Edith’s toys and the chess game that Ina had been trying to teach Alice when they had first been deposited in the room earlier that morning, before Alice’s escape, capture, re-desposit, and assignment of housework.

Alice paced around the parlor, looking into corners and behind chairs.

“What are you doing?” Ina asked.

“Looking.”

“Looking at what?”

“Everything.” Alice was never allowed into the small parlor, which was rarely used. Alice peered at the silhouettes and the paintings on the walls. Dozens of stern faces looked down at her, intermixed with castles and churches.

Ina said primly, “Mother said we are all related to the people in this room, and we should always remember that our actions reflect upon them. Their greatness reflects on us, so we should do our duty and reflect it back to them—oh, Edith. Don’t put that in your mouth.”

Alice sighed, stomped over to Edith, and took the pawn away from her. Edith burst into tears.

“Now see what you made me do,” she told Ina.

“I did no such thing.”

“You did, too.” Alice grabbed the rest of the chess set and put it back on the sideboard while Edith howled.

“Give her a sweet,” Ina said.

Alice sat in one of the fancy chairs and crossed her arms over her chest. “I don’t mind the sound of her crying.” She looked at the ceiling, trying to see if there were any spiders she could capture and drop onto the back of Ina’s fancy chair.

Ina closed the book with a thump and picked up Edith. “Don’t cry, little mouse.” She pulled a tin of pastilles out of her pocket and gave one to Edith. “Only one, now, or you’ll spoil your luncheon.” Edith, well-trained, popped open her mouth and sucked contentedly.

Alice jumped out of her chair and stood next to Ina as she put Edith back on the floor in the middle of her overturned toys. Alice opened her mouth like a small bird.

“Oh, Alice,” Ina said.

Alice sniffed and whimpered like a baby about to burst into tears and rubbed one fat finger under her eye, just like Edith would insist on doing. Ina laughed and gave her a pastille. “You are such a naughty little kitten,” she said.

Alice purred and rubbed her head against Ina’s arm, then set the chess pieces to right again. “Will you play with me?”

“I’m reading,” Ina said.

“You’re always reading. It’s dull.”

“It is not.”

“It’s dull for me.”

Ina sighed and closed the book, this time quietly, with her finger in between the pages to mark her place. “All right. I’ll tell you a story then. But only a short one, and then you have to play with Edith and keep her amused and not let her fuss.”

“All right,” Alice said. She sat on the floor next to Edith, puffing up twinkling clouds of dust, which would have made Mother unhappy, although Alice thought it rather clever of her, using her petticoats to dust the rugs. She picked up the scattered toys and set them within Edith’s reach in rows, as though they were her audience at a play or her soldiers in a war. Edith wiped out a row of them with one cruel gesture.

Ina announced, “The photographer, Mr. Dodgson, is a zombie.”

Alice squealed with delight. “Oh! Is he?”

Ina snorted. “Yes. And that’s the end of the story. Remember, you promised.”

Alice gaped at her. “That’s not a proper story.”

“It is, too.”

“No it isn’t!” Alice shouted.

Edith’s face screwed up. “All right, hush. Mother said that he was infected years and years ago, but nobody knew, because it was dormant.”

“What’s dormant?”

The corner of Ina’s mouth twitched. “Hidden under a rug. Door-mat.”

Alice leaned forward and slapped Ina on the leg. “That’s not true. Stop making up words.”

Ina pulled her stockinged leg out of Alice’s reach. “It’s a real word.”

“It is not.”

They sulked, with Ina reading and Alice setting up the toys again, until the door opened and Mother swept back into the room, knocking all the toys over again. “Girls! Mr. Dodgson is here.”

Alice groaned and started to set the toys aright.

“Up, please. Off the floor,” Mother said.

Ina put her book on the little table beside her, and Alice jumped up and stood next to her. Ina poked her in the side and pointed, and Alice bent over and picked up Edith, who opened her mouth and started crying.

“Give…her…a sweet,” Ina hissed.

“I don’t have any,” Alice whispered back. “You have all the sweets, you selfish cow. You give her one.”

The gentleman who had followed Mother into the room coughed softly into his glove, and the two girls looked up at him, leaving Edith to cry as she would. Really, there was no stopping her for long, and the two of them had simply learned to ignore the noise unless adults were around.

Mr. Dodgson was very tall, taller than Father, and quite thin. He had brown hair that was nearly as long as Alice’s (hers had been cut quite short after the hedgehog incident) and stopped near his chin.

“Are you a zombie?” she asked.

“Oh, Alice,” Ina moaned.

Mother reached towards Alice to get at her ear again, but Alice stepped behind Ina and switched Edith to her other side. Edith was as fat as anything, probably from all the sweets that Ina had given her, and made a good shield against being pinched or poked.

The man coughed into his glove again, this time a little more loudly. After a few seconds, he said, “I’m…afraid so.”

“You’re afraid of being a zombie?” Alice asked. Edith was wiggling to get down, so she let the baby slither down to the floor and pick up a toy, which she chewed between bouts of sobbing. As Mr. Dodgson was standing quite close to them, Alice noticed that his left leg was manacled to a heavy ball, which he apparently dragged behind him. “Have you been press-ganged?” She had heard all kinds of stories about people doing things they oughtn’t, then waking up the next morning to find themselves turned into zombies and press-ganged onto a ship with a heavy cannonball chained to their legs, so if they tried to escape they would sink over the side of the ship and be forced to walk along the bottom of the ocean for ever and ever, because zombies didn’t die, not unless they were spiked in the back of their heads with a horrific crunch! Alice had always wanted to see a zombie spiked, but she supposed that Mother wouldn’t allow her to try it out on Mr. Dodgson, or not until after their pictures had been taken, at any rate.

“Ah, ah, ah, yes. I mean, ah, um, no.”

She wasn’t sure whether he was laughing at her or not. “Which is it?” She took a deep breath to see if he smelled bad. At any rate, something smelled bad, but it might have been Edith.

He giggled into his hand.

“Don’t do that,” Alice said. “I don’t like it when people laugh at me instead of answering the question.”

He coughed, then lowered his hand.

“Oh, I’m a zombie,” he said. “A perfectly tame zombie. B-but I haven’t been press, ah, press-ganged. I’m a terrible sailor.”

“You were press-ganged into taking pictures of us,” Alice declared. “I’m sorry that your whole life has been ruined for nothing, because I don’t want to have my picture taken. It’s dull.”

The man laughed deep down in his throat, making a half-gargling sound as Mother got Alice by the ear again, Alice having quite literally lowered her defenses.

“Ow!”

Mr. Dodgson said something about going outside because of the light, and Ina leaned over and whispered, “You’re in for it now.”

Alice kicked at Ina, but as Mother was dragging Alice by one arm into the hall, she missed.

“Come with me, girls,” Mother said. “Let’s do finish this quickly, so Mr. Dodgson can get back to his…other tasks.”

Alice, stumbling along after her mother and twisting around to see behind her, said, “I thought you weren’t supposed to call zombies Mister any more. In all the stories, they’re called the former Mister or arghhhh a zombie run!”

“That was before the serum that allows us to retain our presence of mind was invented, my dear Miss Alice,” Mr. Dodgson said, clearing his throat. “Now, if one remains calm and refrains from eating anyone, one may retain the title of ‘Mister.’ However, if a zombie attempts to bite one, it’s quite proper to begin one’s address with a blood-curdling scream.”

Ina, with Edith on her hip, carefully closed the door behind them and stayed away from Mr. Dodgson’s iron ball, which he dragged behind him, making him walk with a lurch.

“Like this?” Alice let out an earsplitting shriek that made him cover his ears and open his mouth in mock-horror.

“Indeed,” Mr. Dodgson said, as Mother nipped her ear sharply again.

—

Taking photographs wasn’t quite as bad as Ina had made it out to be. Alice had suspected that Ina had been lying about one or two things, and, as it turned out, Alice wasn’t frozen as a statue for ever and ever, so there. Mr. Dodgson made it seem like a game as he and Miss Prickett set up a carpet and a chair in the garden while Mother watched.

“Why can’t we take pictures inside, if we’re going to make it look as though we were inside anyhow?” Alice asked. Mr. Dodgson had asked her to sit on a chair so he could try to focus the camera. She kicked her legs back and forth.

“Alice,” her mother hissed. “Sit still.”

“That’s a good question,” Mr. Dodgson said. “The answer is that cameras are not nearly as good at seeing things as your eye is. Your eye takes a picture with just a blink, like this.” He blinked owlishly at them.

“I can blink faster than that,” Alice said, blinking dozens of times, her eyelids fluttering.

“Your eyes work better than mine, then,” Mr. Dodgson agreed solemnly. “But even my eyes work faster than this camera. In addition to being quite slow, it sees rather poorly in the dark, and even the bright daylight of the parlor is too dim for the poor thing.”

“It’s quite stupid, then.” Alice glanced at her mother, but Mother had become bored with them and had wandered off, checking on the work the gardeners had done; some new roses had been put in, but they hadn’t been the ones she’d wanted, and she was working herself up to being quite cross at someone other than Alice, which was rarely a bad thing.

Mr. Dodgson leaned forward toward her, and she found herself taking a step backward. He mightn’t look like a zombie, but that didn’t mean he wouldn’t eat her. He whispered, “Yes, but don’t tell the camera it is stupid. If you get it to crying, I won’t be able to take a clear picture for a month. It cries even more than your sister Edith.” Then he leaned back.

“How did you become a zombie?” she asked. “Have you eaten anyone?”

“Oh, no,” he reassured her. “I have never eaten anyone, although I did have the misfortune to see someone eaten.”

“When was that?” Alice asked, leaning forward.

“At Rugby School,” he said.

Alice nodded. She had once overheard her father saying that Rugby was nothing but a pack of beasts, although it was better than it had been, so very long ago. “How old are you?” she asked.

“Twenty-four.”

She nodded again, because that was very old, and tallied with Father’s report of Rugby.

“And how did you become a zombie?” she pressed.

“Hm,” Mr. Dodgson said. “I should be quite happy to tell you, on one condition. The camera is all ready. If you should sit in the chair like so, I will tell you that story. While I am talking, that is the time it takes for the camera to blink. As you recall, it does take a terribly long time, almost a full minute, for the camera to blink and take your picture.

“However, during the story, you must be terribly, terribly careful not to cry, for it is a very sad story, and if you should cry, well, that would ruin the picture and we should have to start all over again, and you might even get the camera to crying, and then who knows where we should end up.”

“Should I hold my breath?” Alice breathed until her chest felt like it would pop and held her breath with her cheeks puffed out.

Mr. Dodgson coughed into his hand again, and she scowled at him. “No, no need to hold your breath. Just breathe very shallowly, as though you were pretending to be dead.”

“Hmph,” Alice snorted, but she liked the idea very much: to pretend to be dead while listening to a zombie tell a story about how he was turned into a zombie. “Do you breathe?”

“I do,” Mr. Dodgson confirmed, making some last few adjustments in the darkness of the cloth covering the back of the camera. “But not as often as I used to.”

“Then press-ganged zombies would drown if they were thrown off a ship,” Alice exclaimed.

“Oh, no. They simply would be unable to speak very well until they had come up to the surface again. Now, let us begin the picture and the story. Remember, it is vitally important that you make not a single change of facial expression until the story has finished.” And then he removed the cap.

Here is the story that Mr. Dodgson told, as Alice sat in front of the camera and listened. (Despite her mother’s complaints to the contrary, Alice did listen most of the time. However, she was of the opinion that listening didn’t oblige her in any way to do what she was told.)

* * * * *

One day, as I was attending school in Rugby, I happened upon a dark hole in the middle of a field. The hole hadn’t been there the day before, and, as you will see, it wasn’t there even an hour after I left it.

I was laying on my stomach over the hole and reaching my arm down with a stick to see if I could reach the bottom, when suddenly I saw a white rabbit running toward me. My experience had previously been of rabbits doing the opposite: that is, running away as fast as possible. “Curiouser and curiouser,” I cried.

The rabbit, apparently not even noticing I was there, ran bang-on into me and bounced backward, unable to take another step for fright.

I looked up to see what could have possibly scared it so. Charging toward us was a maddened zombie, quite ready to eat any body it should happen upon, and it seemed only too glad to see both Mr. Rabbit and myself.

I jumped to my feet with only the stick as a weapon. I swung the stick at the zombie as though it were a sword: one, two, one, two! However, the stick snapped in half, and I was left defenseless. I stood my ground and dared the zombie to do its worst.

Just then, the rabbit gave a roar (if you have never heard a roaring rabbit, it is quite memorable) and attacked the zombie! You see, the poor thing had been bitten earlier and was starting to turn into a zombie, no serum having been administered.

I took a step back and stumbled, almost falling down the hole. The rabbit and the zombie wrestled for a few moments, the rabbit too light to do much damage, but the zombie unable to dislodge the rabbit from his throat.

Fortunately, the zombie took a step too close to the hole, and down they both went. I went back to the school, and one of the other boys noticed that I was bleeding. I went to the headmaster and told him the story of what had happened, but by then the hole was gone, and I taken to the doctor and given the serum before I should change into entirely the wrong sort of zombie, and do say you believe me, or else I should be terribly sad.

* * * * *

He had put the cap back on at some point during the story, but Alice hadn’t noticed. As soon as he stopped talking, she took a deep breath—towards the end of the story, she’d been holding it.

“That was longer than a minute,” she said.

He gave her a little bow. “I entirely agree, my dear, but I did so want to finish the story. However, now I must go and develop the picture.” He disappeared into the little tent.

Alice looked around her. The black tent on the garden grass was sitting right where they usually set up their croquet game. Mother was nowhere to be seen; Miss Prickett was working on a basket of torn things that were usually Alice’s fault, or so Miss Prickett claimed; and Ina was reading a book while Edith began to crawl off under the bushes.

“No, Edith,” Alice said. “There might be rabbits under there. Come away.” She scooped up the little girl, then carried her over to Miss Prickett. “You might take better care of her,” she said, and went looking for a stick.

If there were zombies about (and not the nice kind, like Mr. Dodgson), she would be the first to attack. One couldn’t allow one’s friends to be bitten. It simply wasn’t done.

—

Part 2 of The Queen of Stilled Hearts resumes in 1860, with the arrival of Queen Victoria for a royal visit, as well as a bout of croquet in which Alice loses her temper. Now available at Amazon, B&N, Smashwords, Gumroad, Kobo, and more.

—