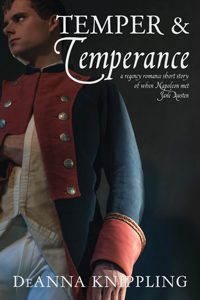

Universal Buy Link | Goodreads

Once upon a time…

Napoléon Buonoparte did not ally himself with the armies of France during the French Revolution, but sought power instead in Britain, where his subtlety and planning was met with reticience and phlegmatism. The British feared Napoléon’s infamous Corsican temper, and worried that it would lead him to vendetta–and not capable leadership. Would he betray them to France unintentionally?

Although he had proved himself capable in various matters, Napoléon knew that he would be once again tested before the British would commit.

His plans hung upon the outcome of a single ball: a man who could not organize a pleasant country ball surely could not be relied upon to lead an army.

His plans were in place, his resources martialed…

…and then he met a bookish young woman named Jane Austen.

This short, sweet romance is an alternate history of what might have happened, if Napoléon had not met his Josephine and gone to France, but allied himself elsewhere.

…

Napoléon Buonaparte, of Casa Buonaparte, in Ajaccio, Corsica, was a man of such seriousness of character that, once he had decided that Corsica did not belong to the French, he could not rest until he had himself taken possession of it.

The inhabitants of Corsica are well known for their tempers, which sometimes erupt into that particular Mediterranean code of honor known as the vendetta. It is widely agreed that if only the inhabitants of that island could agree to end their disputes, they are of such a particularly assured and inflexible character as to be able to conquer the world. But, as the people of Corsica like to say, no-one can hate a Corsican like another Corsican, and the feuds that might have conquered Europe are instead a source of grief for the mothers, wives, and families of those noble souls over-afflicted by their own honor.

Therefore Buonaparte, not having a disciplined army of Corsicans with which to expel the French, turned to the British in order to obtain one. The British had already put off answering the Corsican Question, as it was called, during the French invasion in 1769 (which also happened to be the year of Buonaparte’s birth), and found themselves similarly unable to resolve it when first Buonaparte began to ask it again during the years of 1789 to 1792.

For if the character of a Corsican is marked by his temper, then the character of the Briton shall be known by his reluctance to have one, and to remain untouched by questions of justice and injustice, until such a time as it must be answered upon his own soil, whether in Britain or her colonies.

The British, as led by Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, almost began to think of taking it upon themselves to answer the Corsican Question in 1792 after the Battle of Valmy, in which the Prussians narrowly defeated the French. But we had soon once again resolved not to be too hasty, having only had twenty-three years in which to debate whether or not to assist the Corsicans in throwing off their French masters.

The French, in honor of their narrow defeat in Valmy, began to reverse or at least reconsider some of the changes wrought by their Revolution. Many of the worst excesses of the Ancien Regime had been ameliorated and the Third Estate had taken control of the government, and so Louis Capet, much like a badger that has dug itself under the foundations of a house, was left at Montmédy, well-watched by the dogs, that is, the regular French army.

Meanwhile we Britons, shocked by the intemperate treatment of the French royalty by the French, finally began to wonder if the French Question should be addressed, and rather sooner than later. Mr. Pitt’s government resoundingly vowed to hedge their bets and undermine the most radical and violent elements of the French Revolution by supporting those who would resist them, at least in sending them whatever aid should be determined to be as clandestine and as cheap as possible. Of course, by the time the funds were applied, the main concern was no longer the French and their cries of Liberté, égalité, fraternité! but the Prussians and their push to annex all of Europe and parts of Russia as “traditional provinces of the Holy Roman Empire,” while denying Rome and unifying the Protestant churches in the lands so taken.

Once again, Napoléon began to press for an answer to the Corsican Question, this time promising to send such Corsicans who had proven themselves skilled at the vendetta into lands controlled by the Prussians to cause trouble there.

Thus it was in September 1795 that Mr. Pitt asked his cousin Lord Grenville, the Foreign Secretary, to have a word with Mr. William Wickham, a commissioner of the bankrupts, to place a certain suggestion into the ear of Buonaparte, that if he were to present himself on a certain date in December of 1795 in the town of Basingstoke, Hampshire, at the home of Edmund Fry, a type-founder to the Prince of Wales, then he should be almost certainly assured of the practical details of his plans reaching the ear of the Prime Minister, sooner or later.

In order to prevent any suspicion of collusion between the Corsicans and the British, Mr. Buonaparte, who was the son of a well-off family in Corsica, took a house in Basingstoke in order to see whether he liked the area and the shooting. He firmly denied any intentions of finding an English wife, which meant it quickly became established fact that he intended to take one.

The inhabitants of Hampshire, being firmly convinced of the superiority of the views, the comfort of the house that Mr. Buonaparte had taken, and the fine appearance and temperament of their daughters, accepted Mr. Buonaparte into the community under the unspoken condition that he choose from among them a sensible and pretty young wife.

To read more, click here!