The history of the Grandhotel Pupp has stretched from the dawn of the eighteenth century all the way to modern times. You can see it in movies symbolizing the epitome of wealth and elegance; it is one of the inspirations for the movie The Grand Budapest Hotel. The James Bond movie Casino Royale was filmed there, as was the Queen Latifa movie The Last Holiday. Its current appearance is designed to evoke a sort of worship for excess and status, via a style inherited from the Roman Catholics thumbing their noses at Protestant austerity. It was once a hospital for German officers during World War II, then helped lure tourist dollars into Czechoslovakia during Communist rule. Movie stars flock there in July to attend a famous European film festival. And during the COVID-19 epidemic, it has been forced to close, holding its breath in anticipation of its clientele’s return.

Our story begins under a different name. The earliest part of the hotel began in 1701 as Saxony Hall, built by the mayor of Karlovy Vary, also known as Carlsbad, as part of the Duchy of Bohemia, a part of the Holy Roman Empire (which was formally dissolved in 1806). The Saxony Hall served a ballroom for nobility. Later, in 1708, another mayor build a second hall, the Czech Hall, at right angles to the Saxony Hall, as a competitor for the noblemen’s trade. Descendants of the first mayor’s family built another building at the corner of the two halls in 1730, calling the corner-shaped building “The House of God’s Eye.”

In 1775, a Czech named Jan Ji?í Pop (or Johann Georg Pupp in German), a confectioner by trade, married his employer’s daughter, Františka. With her dowry, she purchased a third of Czech Hall from the widow of the second mayor. All the best people in town being German rather than Czech at the time, the family stopped using the Czech form of Pop‘s name and switched to the German, or Pupp. The Pupps, husband and wife, each bought another third of the hotel by 1778, their success in managing the hall completely overshadowing that of the Saxony Hall next door.

In 1821, there was a flood that ruined the ground floors of both halls; in 1828, a legal dispute meant the Pupp family had to sell Czech Hall to other members of the family; in 1868, Saxony Hall came back into the Pupp family’s hands again, and began buying up all the houses around it, recreating them in 1877 as the Parkhotel, which was so successful that they bought up more property, and built another wing.

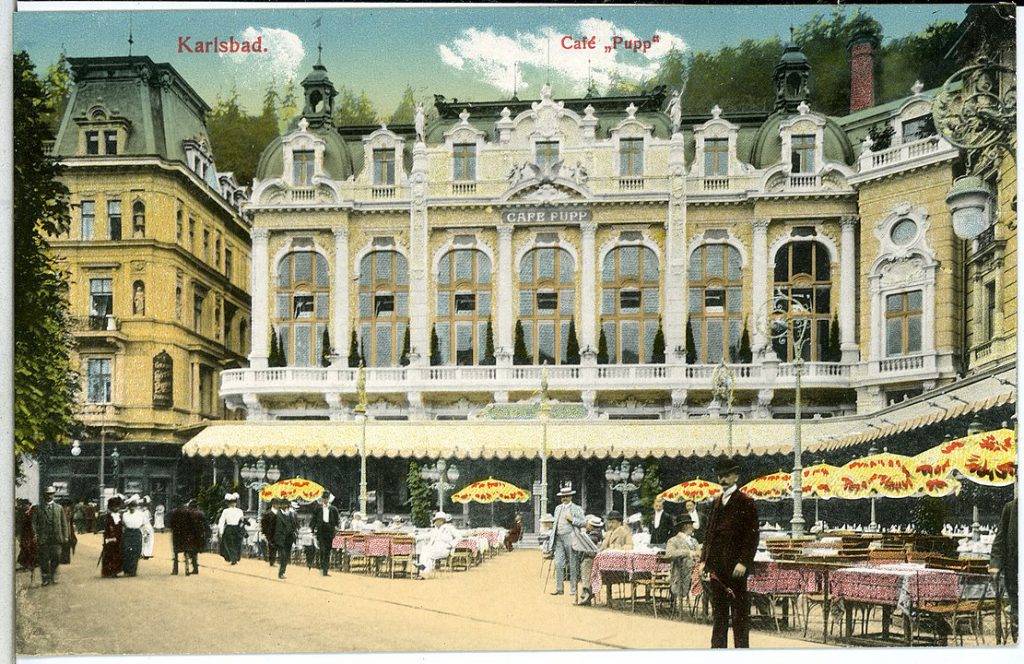

In 1890, the Pupp family finally got their hands on the Saxony Hall, with plans to rebuild the entire complex of hotels in a Neo-Baroque style.

The original Baroque style comes from the Seventeenth century, pushed by the Jesuits as a means for the Catholic Church to combat the Reformation and the spread of the Protestant faith, by creating impressive, highly decorated buildings designed to impress a sense of power, wealth, and tradition upon everyone around it, by taking the ideals of Renaissance architecture and exaggerating them: taller, bigger, more heavily decorated, and more dramatic, with a lot of optical illusions, or trompe-l’oil painting, to create the illusion of even more space to create even higher heavens.

The Neo-Baroque style comes from one of the heirs of Napoléon Bonaparte, Emperor Napoléon Bonoparte III, trying to impress upon the French people that an empire was exactly what they wanted—enough of that republic nonsense! One of the main principles of the Neo-Baroque style has been stated as “leave no space undecorated,” and

The style was so effective, architecturally speaking, that it was copied by most of Europe whenever buildings speaking to wealth, power, and tradition were required: government buildings, churches, universities, and…grand hotels.

The rest of Karlovy Vary seemed to follow suit after the Grandhotel Pupp—although the Municipal Theater may have preceded and inspired it—with different types of fanciful, even gaudy, architecture filling up the town, replacing older buildings and helping turn Karlovy Vary into one of the most luxurious spa towns in Europe.

That luxury did not last forever, although at the Grandhotel Pupp it certainly extended to private bathrooms and hot and cold running water by 1923.

During World War II, the area was annexed by German as Sudentenland, or the part of Czechoslovakia populated mainly by ethnic Germans—an irony for a hotel run by the Pupp family, originally ethnically Czech. Karlovy Vary, long used to catering to the health of its many patrons, became a hospital town, with Grandhotel Pupp (of course) housing injured officers.

By 1950, however, the hotel had been nationalized and the name changed to the Hotel Moskava, while the Pupp family being expelled, along with most of the population of the town, as the Communist-controlled government of Czechoslovakia pushed out ethnic Germans. Once again, the Pupp family was caught by their assumed ethnic identity. The International Film Festival for which Karlovy Vary was famous was started during the Communist years, with the festival eventually switching back and forth between Moscow and Karlovy Vary. The hotel became run down under the communists, but was refurbished in 1968 in order to attract more tourist dollars.

In 1989, the Velvet Revolution overturned the Communist government, the hotel was re-privatized, and the name was restored—although the Pupp family no longer owns it. It is now owned by a joint stock company who made an agreement with the family in order to keep the name, a name that was Germanized in order to appeal to a higher clientele, a name that has been treated as a sort of chameleon, changing from Czech to German, from welcomed to exiled, from ownership to an element of tradition, a way to change a complex history into the illusion of a simpler one: a single name, a single building, a grand hotel.

Karlovy Vary served (and serves) as a quiet retreat a short distance from Prague, the town presenting itself as both isolated and exclusive, even though for the most part, it was neither. Its hot springs and (often smelly) mineral water were touted as having health benefits: purifying the blood, curing illnesses, restoring youth, and melting away excess weight. And fully half of the current Grandhotel Pupp’s rooms are, while expensive, simple, small, and unassuming, small enough and cheap enough to serve as an affordable luxury, one that I know has been more or less created by a façade of stories.

The truth is, Karlovy Vary and the Grandhotel Pupp are not centers of wealth and power. Even today, Karlovy Vary only has a population of 48,000—about the size of Grand Island, Nebraska…Castle Rock, Colorado…or San Jacinto, California. The average income is around US $16,000 a year. It’s a tourist town, a lot like every other, with little industry other than the Moser glass factory and other porcelain, glass, and textile factories. Once you leave the main thoroughfares through the town, it’s a lot of rooming houses and apartment blocks that look too new to be from the Communist era, but were definitely inspired by it.

And yet…

I grew up around tourist towns, vacationed in tourist towns, like tourist towns. There’s a sense of possibility: anything might happen, even being able to pay the rent, or falling in love with a stranger who’s only there for the season, or learning all the stories that happen behind the scenes, from dark rumors to secret dance parties, to hidden caves just off the beaten trail, in the mountains.

I love the fabulous white marble frontside of tourist towns, and the peeled-paint plaster of the backside, too. And to me, the town of Karlovy Vary seems to embody the most romantic, purest form of tourist town possible—and the Grandhotel Pupp, for all its grandiosity, the purest form of luxury hotel to be found in that town.

It’s closed now due to the Covid pandemic. But I’ll keep my fingers crossed that someday fate will take me there, to see both the front and back sides of the house.