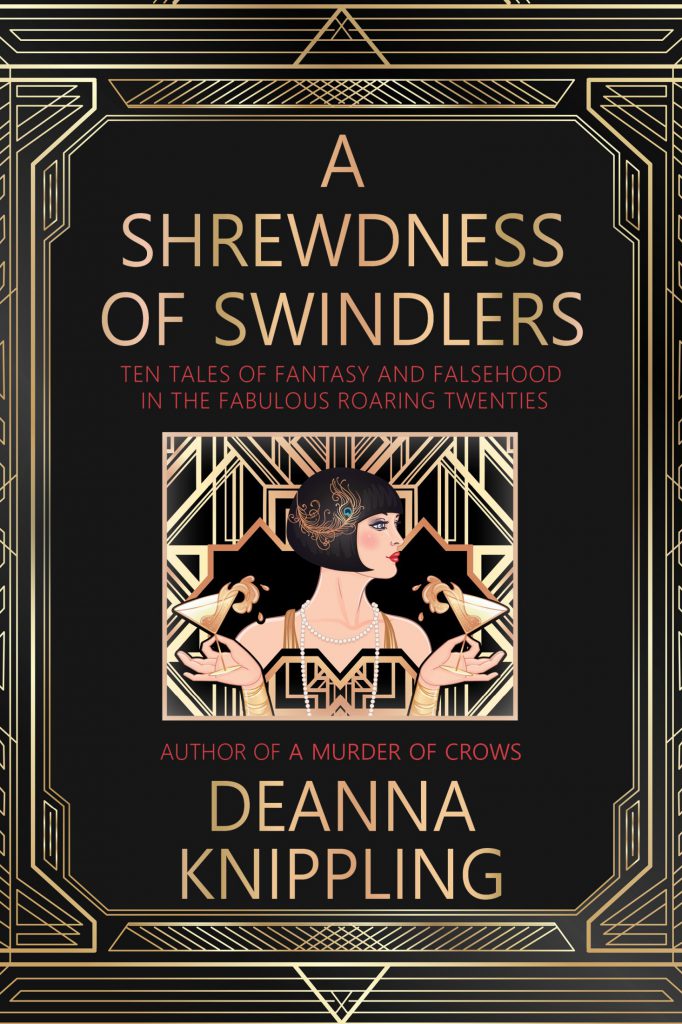

A Shrewdness of Swindlers

Ten Tales of the Fantastic and Falsehood in the Fabulous Roaring Twenties

Dames, detectives, and deception…magic meets the decadence of the Roaring Twenties in ten tales of glitter and jazz.

The year is 1929. It’s two months after the financial collapse on Wall Street, and the world is bating its breath, unsure of what will happen next. Is it the end of an era?

At the Honeybee’s Sting, a speakeasy in the basement of a laundry, a group of unusual figures meets to discuss the past—and perhaps some possible futures: the Detective turned writer, the Dame who’s older than she looks, the Vampire who’s been riding the financial markets for generations, the Spy from across the ocean, the Actress who’s only just learned the truth about Hollywood, and more.

But one of their number is missing, a man connected to the mob, a man who holds the prize for a mysterious storytelling contest—a prize that can give you your heart’s desire.

Ten stories, woven together in the style of The Canterbury Tales, follow the contest along a long, dark night where nothing is what it seems and the best way to tell the truth is to lie.

Pour yourself a cocktail and join us at the liar’s table for the divine, the slapstick, the tragic, the transcendent 1920s today!

Table of Contents:

The Liar’s Table

When Pigs Fly

Myrna and the Thirteen-Year Witch

All the Retros at the New Cotton Club

The Mysterious Artifact

Memento Temporis

The Page-Turners

The Last Word Cocktail

The Man Who Would Sell Fear

The Liar’s Table, Part 2

Sample: A Liar’s Table

The Honeybee’s Sting was a speakeasy back in Prohibition days, in a big brick Lincoln Park building in Chicago. The main floor was a Chinese laundry. Upstairs was Madame Ixnay’s, a house of what you might call ill repute, with eight working girls.

It was a classy joint, as far as those things went.

The bribes it took to keep that place open flowed like the Chicago River into Lake Michigan—polluted and thick.

The Boss was a big man, broad in the shoulders, with a big bushy mustache and dark hair. He had impeccable taste in suits and a knack for getting supplies of decent liquor, sometimes even with the right labels on the outside. He was connected to at least two crime families but somehow managed to stay independent. Everyone knew the Boss was bringing in the liquor via the laundry carts, but as long as the bottles weren’t sticking out from under the piles of towels and bedsheets, the cops pretended not to notice.

The Honeybee’s Sting was down in the basement. The outside of the building was plain brick, nothing fancy. You’d get there by car. The driver would pull up to a door in the alleyway, a huge double steel door stenciled with the words KNOCK FOR SERVICE.

You’d get out of the car, dressed to the nines, and knock on the door with whatever the secret code was that week, and either the door would open or it wouldn’t.

That door was never wrong. There was a lock on it but we never used it. It was just that the door would open…or it wouldn’t.

Like magic.

You’d go inside through a plain brick landing stacked with empty laundry carts, then down some cement stairs to the basement, where there was another heavy door, oak this time. You’d knock the code on the door again, and someone would have to swing it open to let you in.

Light and sound would come spilling out, and the smell of alcohol and perfume and men in heavy coats sweating like pigs, the sound of Black men playing jazz or an octoroon crooning, voices chattering, the sound of glass smashing, of women laughing.

You stepped inside that door and the temperature went up at least twenty degrees. The door slammed behind you, and you were in.

Back then, speakeasies couldn’t afford to be all that fancy, unless they were run directly by the mob. You had to be ready for the cops to seize whatever they could get their hands on. The patrons weren’t too gentle on things, either.

So the Honeybee’s Sting wasn’t all that much to look at in 1929. After Prohibition ended, we fancied it up, but that was later.

In 1929, the walls were open brickwork and the floors were bare cement. A high oak table served as the bar and there were high, round tables around the edges of the room. One corner was cleared for the musicians, and the center of the room was cleared out for dancing. Silk palm trees stood in pots in the corner, half-hiding the spittoons. Bare bulbs hung from overhead on cords.

Behind the bar was a door that led to a reinforced smuggler’s closet that was hidden behind a second door at the back of a shallow safe—not a place you wanted to get locked up in at night, but it did mean that the cops couldn’t get at the liquor stores during a raid.

Opposite the safe was a door to the back room, which used to be the coal cellar. The coal furnace had been replaced a few years ago with a gas furnace that worked more efficiently, and didn’t require stoking.

At least, that’s what everyone said had happened. But I never saw where that gas furnace wasin that basement, or anywhere else for that matter. We had radiators for heat and no end to the amount of hot water for the ladies to wash clothes in, but I never saw a hot-water tank, either. Dom told me not to worry about it.

If the Boss was big, Dom, the bartender, was bigger.

Dom was his own favorite bouncer. If it was busy, the Boss might send one or two guys over to help him, but mostly what they did was answer the door and pour drinks for the girls. I never saw a one of those other guys have to lift a finger against a customer. Dom took it as a point of pride to handle things personally. Word got around. Dom would let loose on some scumbag about once every six months. There was one time Dom cut a guy’s pinky finger off, right in the bar. I put it in a jar of milk to help keep it fresh while he saw if a doctor could sew it back on again.

Dom had an on-again, off-again middle-European accent. He used to talk to the bar itself, and that’s when the accent would come out. “Tair tair,” he’d tell the bar while wiping it. “Is only scratch, noboty means bat. Only scratch.” Then he’d turn around and, in a pure Chicago nasal accent that went straight through your eardrums, would yell, “Hey mister, you gonna get yer fat ass offa that tabletop, or yam I gonna have ta come over and remove it?”

The tables were small, the Black jazz musicians were all right when you could hear them, the girls serving drinks were pretty and had sharpened fingernails, and I washed dishes, mopped floors, swept out spiderwebs, and served as general dogsbody.

They called me Kid. I started working there in 1927 and stayed after Prohibition ended, all the way to 1949 when it closed. Some new folks re-opened the bar in 1993. It wasn’t the same. Whether that was a good thing or a bad thing, I couldn’t tell you. Just different.

The Honeybee’s Sting had a number of incidents worth telling stories about, but one in particular sticks in my mind.

The date was December 29th. Two nights later, it would be one of the busiest days of the year, with everyone out looking to celebrate the change from one decade to another. But the twenty-ninth was a cold Sunday night, cold enough to freeze your spit before it hit the ground, a night so cold it couldn’t snow. It was windy as hell, though, and what snow there was on the ground whipped around like knives.

In short, it was a slow night, even for the girls upstairs. Nobody wanted to go anywhere. Even the jazz trio, always desperate for tips, hadn’t showed up.

And yet that night, the back room had been reserved for special guests.

The back room was darker and damper than the main room and had a low ceiling, just high enough that I didn’t hit my head. Two walls were nothing but rough brick, and the far wall had an old coal chute that had been rebuilt as a back exit against police raids.

When I had come in for the night, Dom had told me, “The Boss wants you to serve the special guests tonight, so the girls can go home.”

I said I was game, and the girls left gratefully. I even got a kiss on the cheek from one of them. Problem was, I was so shy I could barely stutter out my own name, let alone make witty banter. I hoped I wouldn’t have to say much. Maybe the whole thing would be cancelled due to weather.

I finished up my chores early, then sat at a table, reading an old back issue of Black Mask that I had in my back pocket. I reread one of the Continental Op stories, and waited.