New kids’ fiction now available from Amazon, Smashwords, and Barnes & Noble,with other sites to follow (Kobo, Apple, Sony).

I’m trying something new…

This is actually a two-story pack, with “The Test” and another kids’ story set in a fantasy world, “The Scaredy Wizard of Theornin.” Both play around with Grimms’ fairy-tale themes.

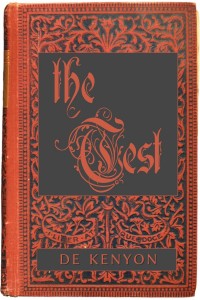

The Test

by De Kenyon

Mari von Ingler is good for nothing, not making sausages or sewing a straight line or anything of use in her village, so her father arranges for her to be an apprentice to a mage…but only if she can pass the mage’s test.

But when the mage arrives, he only sends her out into the forest with no instructions but to come back and tell him whether she passed. She means only to stomp off into the woods and hide for an hour, but now she’s so lost that it would take magic to find her way back…

Mari von Ingler leaned gently against the warm white wall of the inn on the bench made out of half of a tree trunk that nobody but travelers sat on. She didn’t dare move an inch more, or the splinter poking through her thick wool skirt and linen underthings would bite her. She closed her eyes and tried to swallow back the rotten taste in her mouth. She wished she hadn’t eaten Mama’s good food; she wished she couldn’t smell the roast turning on the spit, inside the inn.

She flicked a thumb across her bitten fingernails, feeling the thinness. She’d chewed and she’d chewed and she’d chewed and still they kept growing. She wished become a kind of spirit for a while and hover over herself, so she couldn’t feel anything, only see. Just until after the test. Her fingernails felt like knives made out of paper, cutting if rubbed the wrong way but collapsing if pressed the opposite. Her stomach was full of ants and fingernails, and she felt like a babe about to soil itself.

Who was she?

That was always the question, wasn’t it? Was she a mage, or wasn’t she? Would she pass the test (and did she want to?) and become a wielder of magics, a summoner of demons, a solitary creature that nobody trusted but everyone needed? If she failed, would she be killed or punished or banished? Or—worst of all—would nothing happen to her?

Ahhh, she knew it, that’s what would come.

If so, she’d have to leave the village.

Not because she was too good to live here—she wasn’t good for anything. She was afraid to stay here, with the houses of white plaster and dark-stained wood, with roofs pitched steep to cast aside the heavy snow, saying yes with the smoke from their chimneys. The way it always smelled like manure after the rain, saying yes to the fields. The way the church bells rang, in four notes on Sunday, saying yes, we are here up to Heaven. The way the men drank light-colored beer in large steins decorated with women—yes. The embroidered dresses, the lederhosen, saying yes to giggling girls and yes to flirting boys who never looked her way.

The flowers bobbed their heads in the summer: yes.

The leaves fell with a whispered yesss in the fall.

Winter would come: yes, with the snow, and more snow, and more snow.

Then spring would come with an exclamation: Yes!

And nothing but Mari and the wind said I don’t know.

Nothing was what would happen to her, what happened to all the girls here. They married, they had children, they smoked long pipes and wore bright, embroidered skirts to church and festival days. They were orderly; they belonged. They were yes, dear, and it frightened her.

She didn’t belong in a village of yes.

But there was no other place for people like her, who could not make sausages or cheese or sew a straight line or any other task worth doing, and so if she didn’t run away, they would have to take her in. Useless.

Who was she?

Don’t know.

Ahhh! Her head was spinning with worry. She leaned forward, ignoring the stabbing in her bum, breathed shallow breaths, and put her hands over her head so she would not see when the mage came for her.