So I’m only writing this down because my subconscious is insisting on it; I’ve been struggling with my actual, pays-me-money writing for the last two days straight, trying to fight off the urge to blog about this.

Because it is so supremely nutty.

(Don’t say that, you can’t say that, people will think you’re even more nuts than they already do.)

I’ve found a definition of story, though. And it isn’t even mine, except that it is, because I went on an epic quest to find out something I already knew, and when you do that with something, it’s yours, like a smelly, matted-fur cat with bloody cuts on its paws and a missing tooth, which you have invited in your house with tuna. Even if you kick it out, it’s coming back and peeing on things.

And so here I will claim the idea as my own (it isn’t) and let it move into my writer-brain, and move on with my life.

I’m pretty sure it’s the case that there’s no teaching people what a story is; you have to find out for yourself. And you can’t just look it up; there are no sources that can accurately tell you what a story is. Zeeeee-ro. It’s not that it can’t be told; it’s that we don’t have the ability to hear. Believe me, I’ve tried.

I mean, I just talked to a writer who told me about a session at a recent writers’ conference taught by the guy who writes the Dexter books. He had this exercise where the students would take one story–I don’t know, The Da Vinci Code–and change it from one format to another (fiction to songwriting to a poem, etc.). The idea, as far as I could tell, was that you were supposed to extrapolate story by noticing what fell by the wayside, and what remained.

But no: that doesn’t define story. That exercise, while possibly helpful, would never get me where I wanted to go. I’m too analytical for that. I don’t actually trust that kind of intuitive bullshit–you’re just supposed to know, and if you don’t, it’s because of some flaw in you, not the exercise. Jeff Lindsay. That’s the guy’s name.

(Personally, he struck me as a Conquistador who had found the Fountain of Youth quite some time ago and has been screwing around and bilking people out of money one way or another ever since.

(I was pressed into telling him that–he didn’t care for it, not one bit. I may have turned him off to me personally, though, because before that I was talking to him with a rather conservative writer who went off the deep end with conspiracy theories earlier in the conference, and I suspect he had me labeled as a neo-Nazi after that. I forget what the theory was exactly, but it left a ghastly frozen smile on my face at the time, the kind you get from whatever the Joker gasses you with when he wants to leave an amusing corpse.

(Anyway, no blood no foul, Jeff Lindsay. And South Dakota is a real state, by the way. If it weren’t, then the government couldn’t store all their quasi-mystical crap in a warehouse out in the Badlands.)

So what is story?

I don’t like to come right out and say it; you can’t get there from here.

I’ll give you one of those “what it ain’t” definitions:

It is not a diagram.

If you can diagram it, it’s plot. Or narrative tension (whatever the hell that is). Or emotional arcs. Or character arcs. Or timelines (a.k.a. plot).

Whatever. It’s not story.

Like every single tool you could hand to a writer, diagrams are both a help and a hindrance. At first they help you sort out the mush in your head. But they can only take you so far, and then they start holding you back, and you either ditch that kind of thinking or stay in one spot, forever, like some kind of Greek demigod who got in trouble with the celestial CEOs. Diagrams are hubris, I tell you, hubris.

If it’s a tool, then it’s not story.

Let me tell you, since I’m still not willing to come right out and say the definition, how I got here: my epic quest.

It went like this.

First, I was a kid who ran around and made crap up. I would walk and talk to myself (and anyone who would listen) for hours. I made up some terribly vain things–for some reason, I would spend hours designing dresses in which only my main character would be featured in her adventures; I didn’t care how anyone else was dressed. I thought they were so original, but of course they all happened to have broad shoulders, a v-shape somewhere in the waistline, and a somewhat-poofy skirt. Ah, the Eighties. Those dresses would make me look tough and yet still attractive, and I would have silver hair and silver eyes, because what I really was, was a dragon (let’s not pretend that I thought my parents weren’t my parents, here; it was more that I knew that we were all dragons and they were just too scared of revealing themselves to the outside world to risk telling me).

Instead, my eyesight got weaker and weaker. I have terrible eyesight. No silver involved.

And then, in high school, I ran into a teacher who kindly dragged me kicking and screaming into a writer program in which I was driven to the other side of a state with a group of teenagers who were all more interesting than I was, including the guy with the tan hair and skin, who was a communist and had sai that he brought with him on the trip. Oh, God. I was a boring, introverted kid. Why they even bothered taking me I didn’t know and couldn’t imagine.

I had written a perfectly awful story. When I got there, the coolest person there was a poet, who was also a dancer, who had long, curly black hair. I wanted to be her. Unfortunately, no. Just no. At any rate, I was stuck in a short story workshop when clearly where I needed to be was in the poetry workshop, with my Muse.

I survived that travesty and started writing poetry, typing it on the school typewriters and printing copies on the school copy machines. It wasn’t great, but I got a couple of things published, and at least the school didn’t make me pay for making copies. It was better than the fiction I was writing, at any rate.

Jump ahead: I’ve written so much poetry that turns into some kind of tale that I’ve decided to break down and switch to fiction. I don’t care what anyone says. Fiction is harder. (I’m up in the air about plays and screenplays and comic book scripts.)

Jump ahead again: I’m deciding to stop screwing around, get serious about this writing thing. I vow to write a hundred words a day.

Jump further: I’m publishing an ebook on how the really important thing is to get the words done. A hundred rejections, that’s nothing. Your first million words, that’s nothing.

Jump even further: I’m taking a ton of classes from a couple of professional writers, Kris & Dean, and eating increasingly large (and yet always insufficient) slices of humble pie.

Jump even further yet: I’m at a backyard concert with my husband, I’m a full-time freelance ghost writer who can barely pay her bills, and I’m listening to a singer who’s pretty good but isn’t great, and I’m working out why he’s not great, and I come down to these three principles:

–Stories want to be retold

–Stories want to resonate

–Stories want to be remembered

But I still can’t put a finger on why the guy isn’t moving me, not the way some singers do. He’s good at tapping into existing melody and song structures; the songs sound almost familiar. And yet I can barely remember the song before the current song he’s singing, the songs are pretty to listen to but don’t give me any feels (that’s the current slang for “resonate,” by the way: all the feels).

I’ve been putting together my list of Rs for stories for a couple of weeks now, maybe a month. I threw some other items out, both because they didn’t start with Rs and because I wasn’t getting any juice out of them. When I came up with the “retold” rule of thumb, new things started popping out at me: here was a Cinderella story, there was a high-fantasy Deadpool remake with less cursing. As you do.

The “remembered” rule I came up with a couple of years ago, from reading the submissions pile (slush) of a couple of online magazines. I had forgotten it for a while, but appropriately remembered it. It seems self-evident, although no writer wants to admit their work is forgettable. Forgettable work can be sellable…but it’s gonna get beat down by memorable work every time.

The “resonate” rule is the latest one, which I came up with at the concert–I just wasn’t feeling all the feels. It’s not that I lack empathy, either. (Although I definitely lack tact, which people seem to get confused for empathy a lot of the time.) I was tapping my toe, nodding my head, and enjoying every aspect of the songs. I just couldn’t remember it.

Until the guy got to his last song, and sang something about his goddamn bicycle getting stolen, time and time again. At first he simply complained. Then he admitted it was probably happening because he was kind of an airhead and a dreamer. But finally he really just wanted to know who’d taken his goddamned bicycle. It’s been days now, and I still remember that song.

It also happened to resonate with me: I’ve been an airhead all my life.

Is the song “retellable”? I don’t know. I, personally, have no urge to retell it.

But what, I wondered, made that one song stick out?

It came to me.

Wait…that can’t be right.

I listened to the rest of the song, walked around in a daze, and babbled to my poor spouse all the way home. Yes? No? I remembered that there might be a reference somewhere in the Sandman graphic novels to the same idea, the one I was chasing. I knew who the character was who said it; I even knew the particular storyline and sequence where he said it. (I was right about the character but not the sequence.)

I could tell you now; you wouldn’t agree with me but you might be able to see the rough direction that I was coming from. But let’s wait. Not to build up suspense but to note a caveat:

Human beings can take things that don’t go together and stick them together in such a way that they are a) completely plausible, mentally, and b) compelling, emotionally. So when I say something like “stories want to be retold,” I’m giving an example of that. Stories don’t actually want anything. They aren’t alive. They have no free will.

They’re something, though, that appears to live and appears to have free will–because of how our minds are built. “Rumors have a life of their own,” I can say, and that will resonate. You know it’s true, even though it literally can’t be.

So before I get to my definition, let’s stipulate that a good story takes on a life of its own. That life isn’t like the lives of other stories, not really. Bad stories are a lot alike; good stories–really good stories–are all different.

Sure, they can be retellings of other stories–Shakespeare ripped off everyone. But West Side Story is not Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, which is not Dire Straits’s “Romeo and Juliet.” Not even close.

They share tropes; they share plot and other elements. They’re memorable, they resonate; people rewatch and relisten to them all the time.

And yet they aren’t the same–and not every story based on the same lovers has the same appeal, plot, emotional arc, or even ending. These elements are not the sum total of story.

So when I tell you, keep in mind that people sometimes credit intention and motivation to inanimate objects, like cars, and even nonexistent things, like Justice and Love (which are, by the way, both blind).

…and yet I still don’t want to tell you. I want to listen to covers of the Dire Straits “Romeo & Juliet” and close off here, so that you’ll never know what I figured out, because it’s still not going to mean to you what it means to me, not unless you go on your own epic quest, and then you’re still likely to come back and say, “That’s not it, that’s not quite it…”

But no. The cool thing is that I get to tell you what a story is, and it will still be a mystery. (I think that would please at least one of the characters in Sandman.)

Here it is:

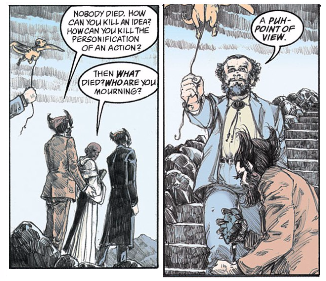

Story is a point of view.

Not, you know, like first person or third person omnisicient. Story is a way of seeing the world. That’s why people say things like “Stephen King could write a grocery list and I’d read it.” Because it isn’t about plot, or character, or theme, or…whatever. It’s about a guy who believes in scaring himself first, a guy who has a serious thing about Maine, a guy who plays guitar in a writer band, a guy who loves baseball and who bought the van that hit and almost killed him, so it wouldn’t show up on eBay.

A point of view.

So while you’re shaking your head and pretending to ponder that (good grief, all that leadup, and that was it?), let me leave you with two things.

First, a link to a great version of Mark Knopfler playing “Romeo & Juliet” with an orchestra. Because I don’t want this self-indulgent blog post to be a total waste of your time. And second, the panel from Sandman (spoiler alert):

I think I finally get it.

(It’s okay, Abel. I first read that line in 1997 and I didn’t get it then, almost eight years after I started my quest, and I didn’t get it for another nineteen years after that. I’m not spoiling anything.)

You and me babe, how bout it?