Amazon | Publisher Site | Goodreads

Author Facebook

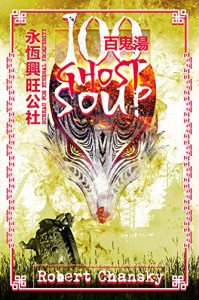

Welcome to author Rob Chansky, who recently published Hundred Ghost Soup. I received a copy from his publisher in exchange for a fair review; you can find the review here. I liked it so much that I decided to beg for an interview. You can also read previous interviews with Megan Rutter and Philip Adams.

1. When I first saw Hundred Ghost Soup come out, the first thing I thought was, “Okay, is this book going to be a superficial treatment of China? Is it going to feel thin and fake? Should I be scared?” Fortunately it was immediately obvious that this wasn’t the case. My question is this: the world of Hundred Ghost Soup is rich enough to point almost toward obsession. What drove you to build it?

I think there are three reasons, and they all boil down to luck, both good and bad.

Foremost (of the good fortune) is my daughter Sophia, who we adopted from China in 2005. The adoption process was a bit like entering (the movie) Spirited Away for real. Then came the part where you’re living with a being new to both the world and this country. A tiny girl, feeling so lost, who smelled like coal smoke for weeks. At that point I was happily writing a book about a mechanical elephant made by an ancient alien Mughal and I didn’t want to be bothered by this young man with the big square glasses who sprang fully formed into my creative life. But as our daughter grew, the urge also grew to tell a story just to her (and whoever else might want to read it). Eventually the desire to do this overtopped the current project, and at some point I couldn’t resist it anymore. Stepping back from a book was a bad writing-career decision, yet one I don’t regret. So I began the Meiren saga—at its end. Not Hundred Ghost Soup, but the last book in this series, although I didn’t know it at the time.

Sadly that story (the last day of Meiren’s career) got bogged down and I decided I needed to answer the question of Meiren’s origin, so I thought I’d start with how he got his name. Just a short story, something to settle those nagging questions so I can get back to it. And that short story became Hundred Ghost Soup. Stepping back from that other book should have been a bad writing-career decision, too, and I don’t regret it either.

So you can see that planning and foresight really aren’t my copilots here. I expect to do better in the future.

My third bit of fortune (a mix of good and bad) was a complete lack of confidence in writing about China. The Chinese say no illness, short life; one illness, long life. Knowing the lack I started reading. When I had a shelf of books read I felt competent to portray someone who lives there. I was writing the book the whole time, though, and had to revise it as I learned. Do I know enough about China now to live there? Not a chance; I only picked up a few things. China is far more complicated than I can imagine. I’ve explored a couple of alleys and talked to some wise people; I don’t live there.

Along the way the wise ones were: Lin Yutang, whose sharp and happy writing voice (particularly in The Importance of Living) was the inspiration for Meiren’s; Barry Hughart whose Bridge of Birds and sequels inspired my writing; and Earnest Bramah’s Kai Lung character.

Now my daughter’s just old enough for me to pester her to read it. “It’s weird,” she’s said. I guess that’s all I’ll get for a while. But she’s got a long life ahead of her. One day I’ll be gone and she’ll have that to read.

2. I’m struggling for a way to phrase this. On the one hand, the story feels very ancient with a modern, somewhat surreal skin slapped over it (I kept getting startled when people sent emails, for example). And yet on the other hand, it seems very postmodern in its sense of uncertainty, more like something Kafka would have written or a Chinese version of A Series of Unfortunate Events. There are so many quick twists and turns that it seems impossible to read this book without an eye to modern thrillers, too. Your approach works–but why was this the approach that you took?

So there are three Chinas: the Old China, traditional with Confucian values and Taoist superstitions; the New China, Byzantine in its entrenched communist bureaucracy; and what’s called the New New China, a strange capitalist (except in name) wild west with the trappings of money, greed and lust for power that call to mind the USA’s rail baron age. Many Chinese live in one or two of these Chinas, and Meiren has to navigate the tension among all three. The environment for telling a good story is richer than any other I’ve touched.

Maybe for the next interview, if there is one, I’ll try to pretend I planned it all. The fact is I let the thing grow and took opportunities as they came. I didn’t direct or plan the book. Perhaps I was just portraying the busy conflict going on in myself (my traditional spirit, bureaucratic heart, and modern mind) and I lucked out that it happened to correspond well enough with actual China that the story clicked together there.

And the way it all wrapped up rather neatly at the end? How the hell did that happen? Until I wrote the scene, I had no idea how Meiren got his name. I’m still not sure how I deserve to have finished a book so tidily, considering my appalling lack of foresight and planning. But it worked, and I’m going to pray a lot more and then do it again.

Maybe the upshot answer to your question is simply: my mind’s a mess but it arrived at some complex equilibrium and from that came a book. Uh. Next?

3. Normally I hate first person present tense writing. You pulled it off. Why use it, and how do you make it work?

Early inspiration for this work came from Stross’ Laundry novels, also written in first-person present. There Stross uses a neat trick to get around the limitation of first-person present: he presents it as a journal, and points out that some of it’s been filled in later to complete the story. That worked for me but not everyone.

I began the Bureau world back when first-person present was a bit of a fad. I don’t normally follow fads, because I knew even back then what happens to them. (Hundred Ghost Soup was finished just as rumors flew that editors were refusing first-person present stories point blank.)

I’d love to say that I did it because Meiren is the most human character I’ve ever written and I wanted him to experience life like we all do, and first-person present is the most like all our moment-to-moment experience.

The fact is, I’ve regretted this decision many times, specifically whenever I wanted to do foreshadowing. I love foreshadowing. I feel like my whole life is foreshadowing. I’m in the grocery store and I reach for the peanut butter and the foreshadowing voice says he did not know that overnight his body chemistry had reorganized its allergies and he held his death in his hands. I’d be in the dentist’s chair and get little did he realize she was no cheerful dental hygenist; this was the serial murderess the papers had already dubbed ‘the perky killer.’ The phrase this tastes suspiciously like human flesh occurs whenever I eat beef stroganoff. So yeah, I like foreshadowing. And I can’t do it here. At least not directly.

But I get over my regret, because there’s so much immediacy that first-person present gives you even as it takes away your ability to easily show what happened when your main character isn’t around. As for showing what’s going on when he isn’t around, something’s always come to me, and making up an excuse for why he finds it out has driven the plot handily, so that has always worked out for me. So far.

Those all sound again like pre-planned reasons. But the fact is I felt my way along as I worked on his voice, telling stories and having him talk to me, and he talked in first-person present. He didn’t seem comfortable in any other narrative type.

4. Please answer this as best you can without spoilers. The main character is an orphan. He has an older brother who is minutes older than he is, and yet is an arrogant bastard. It’s almost like Elder Brother is yet another level of bureaucracy that the main character has to face. I have to ask: What is Elder Brother’s problem?

Ha! That’s a fun observation.

When Elder Brother first started out he was a simple foil for Meiren: yang to his yin, the guy who won’t let Meiren stay in his box out of trouble. Meiren can blame Yang for whatever goes wrong in his life. Now that I’ve had years to think on him, I know that this is a two-way street. Meiren had the chance to call Elder Brother on his crap and never did. He had the chance to teach him what Meiren seemed to come out of the womb knowing. Elder Brother might have listened. As a team they might have been far more than they were separately. Instead, Meiren found it too easy to look down his nose at his brother. When Meiren will realize this, he will be heartbroken.

And while Meiren is going through all this agony, Elder Brother is just having fun and enjoying what he can take from life.

Elder Brother is one of those immovable objects that we all have to deal with. It was once a cliché that he’d never change. Then the cliché became that his type of character would reveal sudden, hidden depth and leave you on that note. I’m wondering what the current cliché is.

But mostly this is about Meiren. He’s Tolkien’s hobbit. He’s a Charlie Brown and a Don Quixote and Dostoyevsky’s Prince Myshkin. He can do no martial arts, he commands no one beneath him, he can do no magic of his own. Even his name shows you the lack of regard the world has for him. He has only his wit and a certain worldly earnestness to get him out of bad situations. He is all of us: keeping the world working every day in little and big ways that no one notices.

This series springs from a set of feelings I’ve grown up with. That there is hidden power in quietness. That there’s a foundation beneath the world that we can sense and interact with, and it interacts with us. I can’t tell you its nature. I get the idea it’s different for everyone. It may exist only in our minds. Even if so, it works better to deal with it as if its origin is outside.

And this: few of us get superpowers. Almost none of us command armies or magic. And yet we have to deal with a large and complex and powerful world, and try to get what we want, and failing that, what we need. And yet each of us has something unique we bring to the table.

Meiren’s story is there to help out with that.

5. What’s the plan for sequels? Are there any, if so when, and what kind of stories will they tell?

My upcoming book is The Manchegan Candidate, a Don Quixote in space SF. I’ve just done the first draft and expect to get that out next year. After this I will continue the Bureau series. Hundred Ghost Soup was Meiren’s origin story; next come his career and life:

In Thousand Dream Thief, Meiren now works for Uncle and the shadowy Bureau for Eternal Prosperity. He hopes to take the university entrance exam at last. But someone is stealing the dreams of the politburo. Chasing the Dream Thief through the dreams of the world reveals a hidden war and a pending revolution, and Meiren must assemble a dream army, and lead it, to deal with the threat. But first he’s got to choose a side.

In Tea of the Ten Thousand Things, Meiren embarks on what seems a routine mission to get a magic tea leaf, and incidentally find a home for an orphan girl. But demons of all stripes are after him, and the girl is more than she seems.

6. Is there any note that you’d like to leave your readers on? (Hint: the additional promo question.)

The sequels will have Meiren negotiating the problems of adulthood as he also wrestles with demons, ghosts and more human sorts of corruption. He won’t triumph. But there are more ways to victory than that.

…

Really liked the interview and learned a lot both about the author and his creative process. I have read the book and as a bookseller put it into the hands of readers. Thank you for the thoughtful questions.

I’m glad to hear that you liked it too!

Pingback: Interview with Richard Bamberg, author of Wanderers: Ragnarök – Wonderland Press

Pingback: Interview with M.J. Bell, author of Next Time I See You – Wonderland Press

Pingback: Interview with Jason Dias, author of Life on Mars – Wonderland Press

Pingback: Interview with Shannon Lawrence, author of Blue Sludge Blues & Other Abominations – Wonderland Press

Pingback: Shannon Lawrence Interview: The Business of Short Stories - Wonderland Press