This is part of a series on how to study fiction, mainly directed at writers who have read all the beginning writing books and are like, “What now?!?” The rest of the series is here. You may also want to check out the series on pacing, here, which I’m eventually going to fold into this series when it turns into a book.

…

Last week (figuratively speaking) on “The Fall of the House of Usher,” we worked on the first paragraph and why it might be the length that it is. If you haven’t read that one, you should probably check it out.

You can find a copy of “The Fall of the House of Usher” here, on Project Gutenberg.

So what are the rest of the paragraphs like?

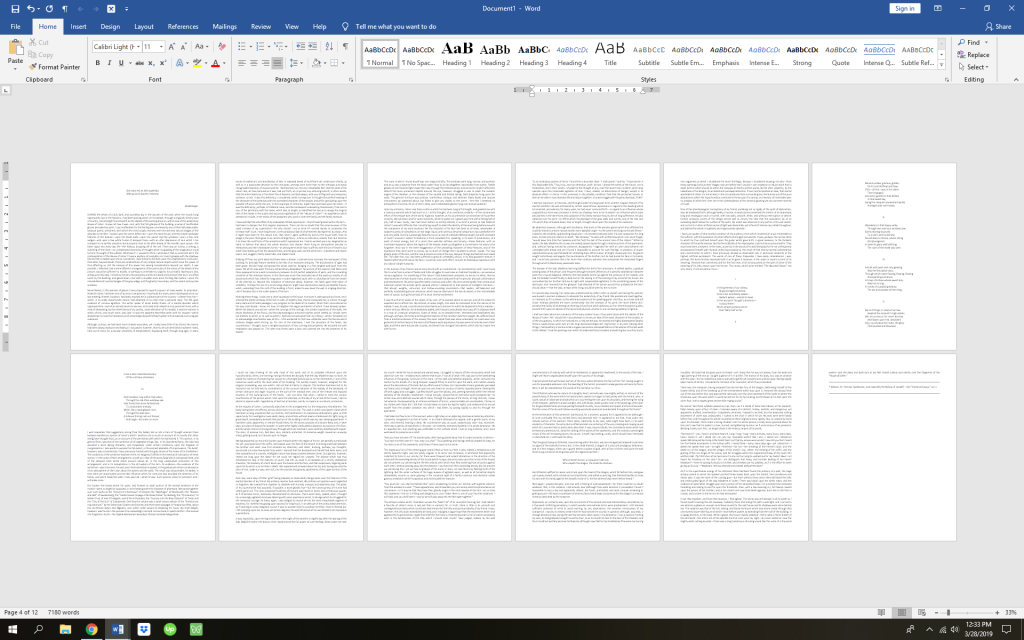

This is the entire text of “The Fall of the House of Usher.” I copied it out of Project Gutenberg, cut off the disclaimers and whatnot, and reformatted it a little so the paragraphs had white space between them to make their lengths more obvious. You should be able to click on the image and pull up a larger version. The text goes from left to right on the top row, then to the bottom row.

What I hope you can see, at a glance, is that the paragraphs here are long.

LOOOONG.

Also, you can kind of see that there’s only one big section to the story, although there’s a poem in the middle of it.

Just from the layout above, we know:

- Long paragraphs are long. (As it happens, the first paragraph is the longest by like 28 words.)

- There’s only one even remotely short paragraph, at 52 words long.

- This is a short story that occurs in one section, more or less, although it may or may not be divided into different scenes connected by transitions. When you go to look at the content, look for what ties this all together.

- The center of this story is the poem. Literally.

- The two set-apart quotes, at the beginning and two-thirds of the way through the story, may be more important than they at first appear (they may appear to have been randomly placed, but they’re the only structural elements, along with the poem, to interrupt the lengthy series of paragraphs).

What we’re looking for are things that make themselves visually apparent, either because they stand out in and of themselves, or because they form patterns.

You might say that Poe wrote in long paragraphs because of the requirements of his day, in which the goal was to pack as many words onto a page as possible. (I have no idea whether this is true, but let’s say it is.) Thus, the lengths of the paragraphs would have no specific meaning, and, if he were writing the same story today, he would have paragraphed it differently.

Which is entirely possible.

However, as most poets know, the form in which one writes affects the contents of what one writes. A pop song is not an aria; a haiku is not a sonnet.

Fiction in which one must pack as much text as possible onto a page is not text in which you’re getting paid by the line. The content will prove to be somewhat different: a tale in which it is encouraged to have long, smooth, almost lulling paragraphs will be more slowly paced than a tale in which short, staccato paragraphs are the norm. A slowly paced story will have different content than a fast-paced one, just as a historical drama like The Remains of the Day will be paced differently, and have different content, than John Wick.

A good author suits their content to their form, and their form to their content. If it works out better to have long paragraphs, then a good writer will write the best slow-paced story they can produce. (An inexperienced writer may try to force a fast-paced story into long paragraphs, and may or may not succeed.)

So what we’re looking at in Usher is a relatively short piece with long paragraphs and therefore slow pacing. The paragraphs tend to stay in the same pattern of long paragraph followed by long paragraph–giving the piece a hypnotic feel. You’ll often see a writer interrupt long paragraphs by one- or two-line short paragraphs to keep the reader from getting fully lulled.

Like this.

Then, in the middle of the story, is something completely different, the poem, called “The Haunted Palace.” (I pulled the numbers out; they’re distracting.)

In the greenest of our valleysBy good angels tenanted,Once a fair and stately palace—Radiant palace—reared its head.In the monarch Thought’s dominion,It stood there!Never seraph spread a pinionOver fabric half so fair!…Banners yellow, glorious, golden,On its roof did float and flow(This—all this—was in the oldenTime long ago)And every gentle air that dallied,In that sweet day,Along the ramparts plumed and pallid,A wingèd odor went away.…Wanderers in that happy valley,Through two luminous windows, sawSpirits moving musicallyTo a lute’s well-tunèd law,Round about a throne where, sitting,Porphyrogene!In state his glory well befitting,The ruler of the realm was seen.…And all with pearl and ruby glowingWas the fair palace door,Through which came flowing, flowing, flowingAnd sparkling evermore,A troop of Echoes, whose sweet dutyWas but to sing,In voices of surpassing beauty,The wit and wisdom of their king.…But evil things, in robes of sorrow,Assailed the monarch’s high estate;(Ah, let us mourn!—for never morrowShall dawn upon him, desolate!)And round about his home the gloryThat blushed and bloomedIs but a dim-remembered storyOf the old time entombed.…And travellers, now, within that valley,Through the red-litten windows seeVast forms that move fantasticallyTo a discordant melody;While, like a ghastly rapid river,Through the pale doorA hideous throng rush out forever,And laugh—but smile no more.

Why?

Here are the other elements that stand out:

The short paragraph:

“And you have not seen it?” he said abruptly, after having stared about him for some moments in silence—“you have not then seen it?—but, stay! you shall.” Thus speaking, and having carefully shaded his lamp, he hurried to one of the casements, and threw it freely open to the storm.

The first quote (at the beginning of the story):

Son cœur est un luth suspendu;

Sitôt qu’on le touche il résonne.

Which translates to:

Their heart is a poised lute;

as soon as it is touched, it resounds.

The second quote:

Who entereth herein, a conqueror hath bin;

Who slayeth the dragon, the shield he shall win.

Why?

Next time, I want to talk about the content of the poem and the two quotes (and the story that goes with the second quote), and why they are formatted differently. Poe could have written a story without a poem at its heart, no quotes, and no shorter paragraph.

Why didn’t he?

…

The world is madness. Read the latest at the Wonderland Press-Herald, here!